|

An occasional series looking at the genesis of a story, from the initial spark of inspiration, through conceptual development, the writing process, and what happens next, with tips based on what I’ve learned along the way. In this blog, I’ll be looking at On the Brink, the sequel to my Arthur C Clarke Award-shortlisted debut novel Edge of Heaven. In spring 2003, I was at something of a crossroads in my life. Circumstances had conspired to make it necessary to leave a job that I adored, and I’d been doing temporary admin work to pay the bills. I’d decided to go back to college in the autumn to study for a qualification in journalism, because I was still trying to find a way to write for a living and I’d had the grand total of one short story published in the entire history of ever, so fiction didn't seem like a viable career option just yet. But September was months away, and I had a whole summer to fill before that. And then I found an advert for temporary factory workers in the Netherlands, and I knew immediately that this was what I'd been looking for. Have you ever had the misfortune of encountering a rotten hyacinth bulb? Until that summer, I hadn't either, and I’m delighted to report that I haven’t encountered one since, but that smell cannot be forgotten. It’s only one of a sepia-tinged marathon of memories that I’ve carried with me in the years since that glorious, sun-drenched summer. The first night, when I couldn’t get my fancy tent pitched properly in the campsite where I'd be living for the duration, and spent long, miserable hours blanketed by the dew-damp, sagging inner skin. The €1 cartons of wine that my friends and I would pick up at the local supermarket, accessed by an idyllic half-hour walk along a flower-soaked lane, and drink on the sun baked grass outside our tents as dusk turned the sky every shade of flame. The beach party where we met our absolutely hammered boss and brought him back to the campsite to try and feed him something so that he’d be able to get himself home in one piece. The day-trip to Amsterdam, nursing a monster hangover and completely failing to find the market that we’d come specifically to browse. The laughter. The camaraderie. The sheer joy of being young and carefree and on an adventure, far from the worries of home. Edge of Heaven was still in its earliest drafts in those days. But that summer, the idea of a sequel began to work its way into my head. Would there still be a need for bulb-packing factories in the dystopian future? And what would they look like? Slowly, the orbital city of Luchtstad began to take shape. This was before I’d discovered that I was very definitely a plotter [1], so I can honestly say that the only similarity between the initial draft and the one that is, as I write this, about to launch at EasterCon 2022 is the fact that they’re both set on a postetheric city and they both star Danae Grant. That earlier tale was set at the very end of Danae’s long life and was a kind of reflective longing for what might have been, in a world in which Turrow is many decades dead. My word, was it depressing. Like the earliest drafts of Edge, Brink was first drafted on word processing software so ancient that it’s no longer supported, as far as I know, and I am 100% fine with that. Some things do not need to be revisited. Did I say “draft”? That’s a little misleading. “Draft” implies that I got as far as a completed MS. I did not. Whether some part of me knew, deep down, that this was not a story that was going to find an audience, or whether I was struck by a dose of good, old-fashioned marathon-of-the-middle [2], that early effort petered into nothing after about 20,000 words. (Again, I’m not going back to check exactly how long it was when I abandoned and you can’t make me.) I found myself distracted by a new and shiny story idea and that was that. For the time being at least. I dived back in briefly in 2009 (and if you’re wondering how I manage to be so specific about the years, I promise you it’s nothing to do with my skills of recall: Edge got a significant rewrite that year because Swine Flu happened, and I got to observe the emergence of a pandemic in real time. That… was kind of a bigger deal back then. So, while Edge was on my mind, Brink shuffled up the ladder of consciousness and I started getting some ideas around it again). Luchtstad got its name at that point, and I found myself writing little vignettes from Danae’s life on the city and gradually getting a feeling about what it looked like, the people and the culture, and how she meshed with all of that. I still had it in my head, at this stage, that I was writing from a point several hundred years in the future and reflecting backwards in time with these small sketches, so they were still plenty melancholic. But, you know, I’ve come to love Danae like a family member. And, while a writer’s job is primarily to torture their characters to some degree, I couldn’t help feeling that I was being… unfair to her. Did she really need to spend her long, long life so lost? All this while, Edge of Heaven was evolving. In 2012, I attended TitanCon with my friend Maeve and got the chance to ask Leigh Bardugo, bestselling author of the Shadow and Bone series, for her advice on revising an unpublished manuscript. She told me to find the person in my life who read widely in the genre and could give good, honest advice and ask them if they’d critique for me. I turned, wide-eyed and hopeful, to Maeve. Bless her forever, she agreed to do it, and she did an amazing job. The revisions I made based on her advice netted the new draft a winning spot on the Irish Writer’s Centre Novel Fair, which led directly to the novel finding its first publisher. Which led me back to On the Brink. In June 2016, I launched Edge of Heaven a full 12 days before I got married – which is not a timescale I’d recommend, in case you’re wondering – and now, with an actual published novel to my name, I was emboldened to start seeking assistance for the writing of whatever came next. The Arts Council of Northern Ireland – Northern Ireland being where I live – runs an Artists Career Enhancement Scheme that awards a grant to arts practitioners to support them in their practice. I applied for funding to pay for time to write the sequel to Edge and a mentorship with bestselling science fiction author Ian McDonald, who happens to live around the corner from me, and the award was granted. I was ecstatic. And then I realised that I’d have to actually write the thing. It turns out that I do not do well with unbroken hours of writing time. I’m not that sort of writer, it seems. One thing I will say for that period is that my house was very clean. Ian was fantastic, though. His mentorship was incredibly generous and enormously helpful – he has a way of asking exactly the right question that leads you to reconsider something that you hadn’t realised wasn’t working, and he also – as an aside – had some excellent TV-watching suggestions. By late 2016, my first child was on the way, due in June the following year, so that seemed like a sensible deadline to aim for, since I suspected it was unlikely that I’d be in the headspace to do much writing with a newborn (spoiler: I was correct). And then things… kind of came apart. I parted company with the publisher of Edge of Heaven in April 2017 after a difficult few months. Writing on On the Brink wasn’t going fantastically and I knew that I hadn’t found Danae’s first-person voice in the draft I’d produced thus far. I strongly suspected that I was going to have to junk the first few chapters completely and start again from scratch. You know that feeling when you know what you have to do but you really, really don’t want to have to do it? Yeah, that. That was where I was when my son arrived, and the rest of that year is kind of… [scenes missing]. But I did it. I junked those opening chapters, and the feeling of relief once they were gone was swift and powerful. I kept the sub-chapters that were in Adam’s voice, so it wasn’t a complete rewrite, and, somewhere along the line, I realised that I’d hit the midpoint. The marathon of the middle was over. I know from personal experience that the section between the midpoint and the start of Act 3 feels like it’s half the length it actually is. Encouragingly (as someone who can be a bit… verbose), my midpoint was sitting at around 55,000 words, which meant that I would not be looking at another monster 135,000-word novel, which, yes, okay, some novels are just as long as they are, but you don’t tend to make any publisher friends if your novel is north of 120,000 [3].

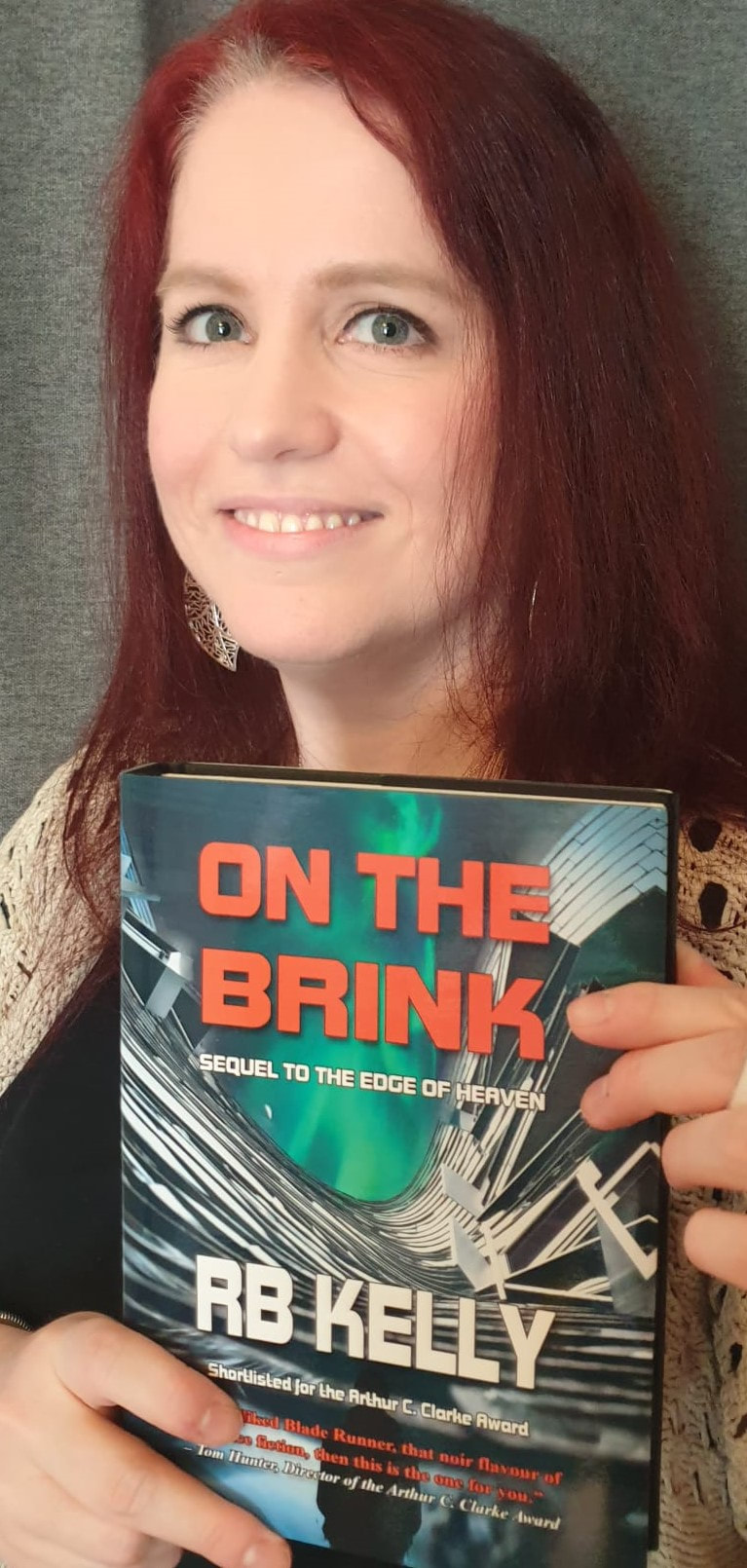

It was a long road from idea to print. But I don’t think that’s a bad thing at all. I wasn’t ready, in 2003, to tell On the Brink as it needed to be told, and I had growing and maturing to do as an author before I could do justice to the story. But I’m looking, right now, at the hardback copies of my second novel on the bookshelf in front of me, almost twenty years after the unforgettable summer that inspired it, and if I close my eyes and let my mind drift back, I can still hear the birdsong in the flower-lined hedgerows of the place that stole my heart and spun an orbital city out of the golden, sun-warmed air.

Tips & Tricks[1] Are you the sort of writer who needs to know how the story ends before you start writing? You’re likely to be a plotter. Learning narrative structure changed the way I write and helped me find the process that works best for me (and this came about largely by accident, I should add: I sort of stumbled across it one day and it seemed like something worth exploring). I always advise new writers to learn the basics of narrative structure, if only to be familiar with how it works, and then file them away in some recess of their brain until they need it again. Are you the sort of writer that needs to write the story to work out what it’s about? Then do not let us plotters tell you that you’re “wrong” and you should be plotting in advance. How can you, when you don’t know the story until it’s written? There are as many writing processes as there are writers, and success lies in working out which one suits you. But I definitely recommend at least familiarising yourself with structure, even if you’re not going to use it in advance, because (a) you’ll need it when you’re editing regardless, and (b) there’s a small but non-zero chance that you might actually be a plotter who just didn’t have the tools to recognise their true process (which is what happened to me).

[2] The marathon of the middle is a term that describes the way novels (and occasionally short stories too) hit a wall at around 15-25% of the way through. Honestly, if I had 5p for every time a student mentions that they’ve started X number of projects but never seem to make it to the finish line – and 10p for every time I correctly guess what stage the projects are at when they’re abandoned – I’d be able to afford a very fancy coffee, at the very least. With flavoured syrups and almond milk and everything. The marathon of the middle is normal. I’m going to say that again: the marathon of the middle is normal. What happens – and this is another reason why it’s a good idea to learn narrative structure – is that your story moves out of the “honeymoon phase,” also known as Act 1, in which you’re introducing your characters, your world, the status quo and the central conflict that’s going to drive the narrative, and into Act 2, in which your character is confronted with a series of obstacles of ever-increasing complexity in their journey from conflict into resolution (which happens in Act 3, at least according to the structure I teach). Act 1 is a lot of fun. It’s fresh and shiny and you’re flush with the thrill of new love. Act 2 is where many stories start to feel like hard work, particularly in the bit between the end of Act 1 and the midpoint. It can feel like you’re pushing a boulder up a hill during this part of the process, and many new writers, not knowing to expect this, feel the abrupt shift in effort and start to doubt themselves, their ability, and the story. Should it be this much work? Does this mean there’s a problem with my writing? Why isn’t this fun anymore? And that, my friend, is why stories get abandoned. There’s no easy solution to this, I’m afraid, but there is a way through. First off, knowing that it’s normal can be a massive weight off a writer’s shoulders. It’s not you. It’s the process. We mostly all feel some variation of this at this point. Secondly, DO NOT ABANDON. You’ll find it much harder to come back to it if you do. But break the process down into manageable chunks: if sitting down to write 1000 words seems like an impossible task right now, do not try to do that. You’ll only get discouraged and entrench the negative feelings. Do 10 minutes here and there, but do this regularly. Make it 5 minutes if 10 still feels too daunting. Stay in touch with your story, don’t panic about the rate of progress, and know that the fun bit is coming back. This really is just a time for showing up at the keyboard and mashing out a few words through a veil of hate if you need to. I promise it won’t feel this hard forever. [3] Oh my. There are just SO MANY wordcount-by-genre breakdowns available on the internet, and your mileage may vary, but here’s what I use as my go-to guideline: <40,000 - novella 80-100,000 - novel 80-120,000 - speculative fiction novel Now, let the arguments commence.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Tips, tricks & advice to help your writing shineCategories

All

Blog updates on the first of every month.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed